Tilford and Stout Scholar: Rio Baran

With the support of the AEG Foundation, I was able to spend the summer of 2023 on my first geology field season in the Australian Outback. There, I pursued questions on the role of early sponges’ (Archaeocyathids) in early animal evolution. Alongside a team of seasoned geologists from Princeton University’s Maloof Group, I set about to study the rocks of the Flinders Range. From sunrise to sunset, I searched the Paleozoic layered sedimentary rocks in the outback to better understand the climatic shifts of the early environment (including potential global glaciations) and the ecologies of 500-million-years ago.

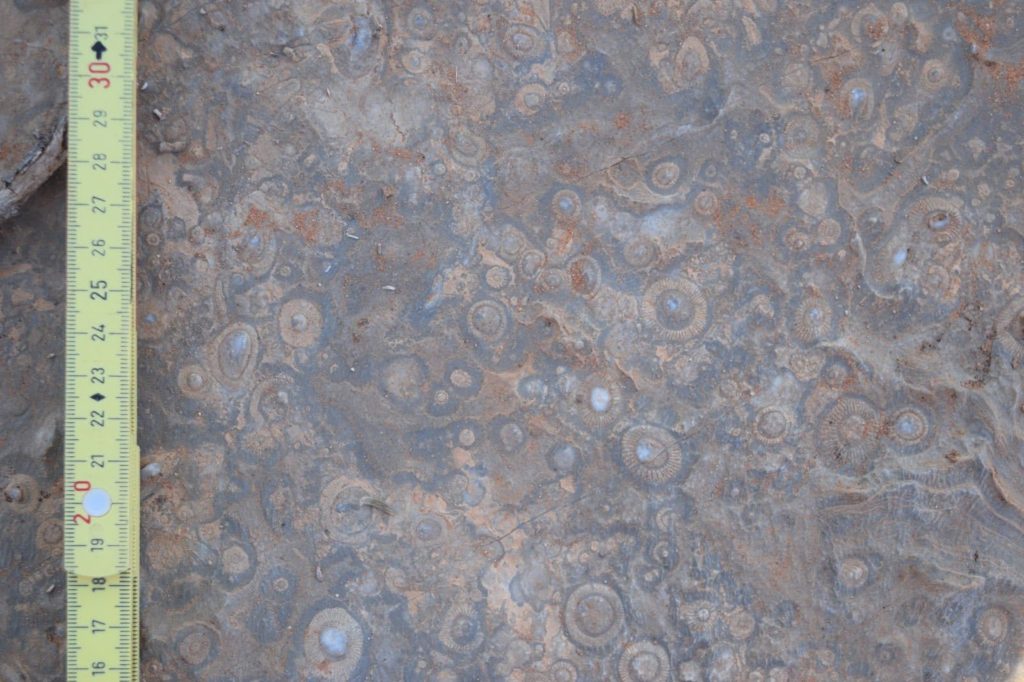

Specifically, my focus was on an archaeocyathid reef from the mid-Early Cambrian.

Before archaeocyathids, there were no creatures that were able to build reefs that significantly altered the flow of water on the seafloor, and their existence aligns with the rapid evolution of complex animal life known as the Cambrian Explosion. Were achaeos crucial to the emergence of complex life? To answer this question, I wanted to know more about archaeos’ role as ecosystem engineers. How do archaeo reefs physically and chemically alter their surrounding environment? Do other organisms take advantage of these manufactured niches? My goal, in short, was to make a map of the Australian archaeocyathid reef.

In the field, I studied the entirety of the reef, which was about 1,000 by 100 meters using multiple scales of observation. I took drone images, collected samples, and recorded observations in multiple transects along the reef. As in much of geology, the area that I had access to was 2D, but represented a 3D environment preserved at different times. Another scale of observation was point counting. The preservation of rock, while subpar in some areas, was magnificent in others. I developed a sampling system to record what was preserved in the windows of rock with particularly good preservation. At each point, I obtained a sample for lab study, GPS coordinates, and other information about the rock. The ability to observe closely and uncover Earth history was novel and magical!

All the while, I was camping in some of the most beautiful, remote locations in the world. I learned how to make an apple crumble over a campfire, I woke up to kangaroos hopping past my tent, and I became skilled at hiking with a backpack full of rocks.

After my month of field work, I returned to the lab at Princeton and got to work sawing, polishing, drilling, and measuring chemical isotopes. Over the course of this project, I progressed from reading literature to asking questions about field evidence, from familiarizing myself with lab equipment (like saws and polishers and mass spectrometers) to coordinating chemical analyses independently. I learned to consider difficult questions and confront unfamiliar situations. I’ve emerged as a fiercer scientist.

I’m so thankful for the funding which made this opportunity possible. I consider the luck and beauty of research made possible by rocks that offer us a window into the past. I think about the poetry of walking through time and space as a geologist. I will carry the practical skills and scientific resilience from my archaeocyathid project through my final year of geoscience at Princeton University and beyond.